Is There a Crisis?

A self-transcendent conception should ideally explain the following four things: (1) what the world is like, (2) what we are like, (3) why the world appears to beings like us in certain respects as it is and in certain respects as it isn't, (4) how beings like us can arrive at such a conception.

(Nagel, "The View from Nowhere")

Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho'

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are, —

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

(Tennyson, "Ulysses")

He went like one that hath been stunned,

And is of sense forlorn:

A sadder and a wiser man,

He rose the morrow morn.

(Coleridge, "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner")

Despite all my rage I am still just a rat in a cage.

(Smashing Pumpkins)

It seems to me that there is an essential dilemma in the scientific endeavor, one that can best understood through the allegory of The Prisoner. Sometime while I was in high school, PBS ran an old British television series called "The Prisoner." I assume it was originally made some time in the 60's. Suffice it to say that it was extremely weird — definitely not what you would ever expect to find on American TV.

During the opening music and credits, we watch this James Bond-like hero character driving a small British sports car into an underground garage, and then moments later striding purposefully down a long tunnel into an obscure basement office (evidently the seat of some unsavory state security operation with which he is affiliated). He has a brief and agitated conversation with the mysterious figure behind the desk before bitterly thrusting down a letter of resignation and storming out. He races back to his apartment and anxiously throws a few belongings into a small suitcase, evidently preparing to make a hasty escape. But someone has other plans for him. A mysterious figure arrives at the apartment, and within a matter of seconds the hero is lying prone on the floor — unconscious from the poisonous gas injected through the door's keyhole.

He awakens some time later, alone in the living room of a strange post-modern apartment. Alarmed and afraid, he rushes to the window, preparing to confront his unknown assailants. But what he sees outside is not a military complex, nor are there any signs of guards, interrogation squads, or other trappings of captivity. Rather, what he sees from the window is a peaceful and almost surreal little village. He is stunned. What exactly had happened to him? Where is he? How did he get here? Confused and angry, he bolts out of the apartment looking for answers. He finds a shopkeeper just opening her store. "Where am I?! What is this place?!" he demands.

The shopkeeper's matter-of-fact reply: "Why, you're in the The Village, of course."

Frustrated, the hero questions several other people, but none of them is any more forthcoming. All they can tell him is that he is in The Village. No one can explain to him where or what The Village is, or how he or any of them came to be there. What is even more infuriating and alarming is that none of them seem to share his discomfort at not knowing anything about their present situation. They show no concern about where they are, how they got there, or why. For that matter, they show no interest in who they are, as they are all referred to by numbers instead of names. (Our hero is Number 6.) These people are simply not bothered by the absurdity of it all — they just go on about their mundane business. For them, "You're in the The Village, of course" is the beginning and end of all knowledge. There are no questions; Everything is perfectly as it should be, and was ever thus.

The story continues from there, and you can trust me when I tell you that it gets much weirder. (The final episodes are essentially incomprehensible.) But the allegory I have in mind relates to the opening sequence of Episode 1 that I just described. Let us consider the Prisoner awakening in his strange Village as an allegory for our own cognitive awakening. Put yourself now in the role of the Prisoner. Indeed, you are the Prisoner, and the Village in which you suddenly and inexplicably find yourself is the World that you see every morning when you wake up. Don't forget that.

Unlike the Prisoner, we do not have the benefit of a sharp moment of discontinuity demarcating the break between a normal "prior existence" and an abnormal "current existence". Rather, we are brought to our current existence by a subjectively smooth and seamless evolution in awareness and cognitive-perceptual capacities. We first enter this world as a primitive creature capable only of seeking food, warmth, and affection. Over a long period of pre-reflective development, we successively add perceptual and cognitive capacities as dictated by a genetic program which has been tailored to provide maximally synchronous meshing of organism to environment. Capacities and parameters that are not evolutionarily hard-coded into alignment with the environment are nevertheless tuned over the course of development by various learning mechanisms to respond in optimal fashion to the statistics of the particular environment on which they are trained. Thus, long before we ever achieve verbal competence or the capacity for abstract thought and advanced symbolic operations, our minds have already been thoroughly adapted, acclimated, tuned, and conditioned to this particular world that we refer to as reality.

It is because of the fact that by the time we achieve our adult mental competencies and the ability for reflection we have already become so well adapted to our environment that there scarcely seems anything worth reflecting about — it is because of this that most individuals are never troubled by what we call "philosophical problems." Certainly, if someone whacked them on the head and they woke up in a Mexican warehouse, they would run about in a panic yelling "Where the hell am I?" But this emotional alarm is only the result of the sharp discontinuity in state that occurs under those circumstances. Because the manner in which organisms are introduced into this world produces little or no subjective discontinuity, few people ever find the opportunity to recognize that there is anything noteworthy about the world and about their place in it. Rather, most humans are so acclimated to their world that they cannot conceive that anything about their existence might be otherwise. Certainly, they can conceive that they might have been born in Africa or China or perhaps on a Moon Base, circumstances permitting, but they will never be able to formulate the essential existential questions:

What the hell am I...

Where the hell am I...

What the hell am I doing here?"

The expletives above are important to indicate the emotional state that must accompany a true realization of the nature of the problem. Like the Prisoner, who reacts to his situation with confusion, anger, fear, perplexity, and ultimately purposeful action, the appropriate reaction to the coalescence of the essential existential questions must be confusion, anger, and fear, and then ultimately a burning desire to find the answers to these questions at any cost. To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield. The Prisoner upon awakening in his strange Village does not say "Oh well, whatever... seems like a nice place to retire." No! The Prisoner needs to know what the hell is going on, and there is no way he can rest until he gets some answers.

In moments when I think of myself (like the Prisoner) as having unexplainably awoken in this strange world, I do indeed become agitated, anxious, frightened. I want to stop everything and demand an immediate explanation. I want to scream "What the hell is going on here!" or "What am I?" I want to wave my hands madly through the air, pointing to everything and nothing and cry out "What is all THIS!?" and "Why is all this the way this is!?"

And I need to have answers now, today — not tomorrow, not next week. How can the Prisoner even think of eating or sleeping when he doesn't know the first thing about his circumstances? And what about you and me? Should we not all run through the streets yelling, "What happened?! Where am I?! What am I?! What the hell is going on?!" Like the victims of an sudden earthquake awakening amidst the rubble, should we not be gripped by the most severe terror, anger, and confusion? Like the Prisoner awakening in his strange Village, should we not furiously demand immediate answers? The Prisoner does not first shave, shower, put on deodorant, prepare breakfast, and only THEN demand an answer. There is nothing of greater importance to the Prisoner than discovering the facts of his present circumstances.

Our first instinct should be to scream.

Strange as it sounds, I think it's fair to view the scientific endeavor as our most effective substitute to screaming. When we feel the existential mystery pressing in on us, there are moments when we indeed would wish to scream at the top of our lungs, "Give me answers! I want answers!" But like the Prisoner, we quickly discover that our impassioned demands, pleas, and threats are met by Nature with contemptuous silence. Whatever is "out there" is clearly not disposed to providing straight answers to straight questions. And when the Prisoner realizes that his captors are likewise unforthcoming, he does not give up. He does not resign himself to being manipulated by unknown forces, he is not happy with his lot. Rather, he takes the offensive. He improvises, manipulates, investigates, pursues every indirect avenue that might shed light on his situation. And so too, when our screams failed us, we found methods by which to improvise, manipulate, investigate — to scratch and claw our way toward some understanding of our own existence. This is science. It is thus far the only mechanism that appears to provide any genuine insight into our circumstances.

But we must remember that while science remains the effective substitute to screaming, it is hideously slow and often painfully indirect. And that is the danger. What we admire most about the Prisoner is that he never loses his passion, never becomes complacent or resigned, at least not for long. He does not becomes entranced and enchanted by the intricacies of his own manipulations and improvisations. While his manipulations may take him far afield and require him frequently to "play the game" as his captors intend, the Prisoner never forgets his own agenda, his own questions... Whenever given the chance he demands, "Who is Number 1?", meaning "Who is in charge? Who has the answers?"

While we scientists don't expect that there is some clandestine antagonist hiding the answers from us, shouldn't the scientific endeavor nevertheless be pursued with a similar atmosphere of panic and urgency? For God's sake, we have no idea who we are or what we are doing here! How do we have the time and patience to train rats, teach undergraduates, or run ANOVAs? Why aren't we confused, perplexed, and angry, demanding answers? Don't we realize the utter mystery of our existence?

I indeed suspect that most scientists have forgotten that they are supposed to be screaming. Perhaps they never knew this to begin with. They, too, like everyone else, have become comfortable with the world of their experience, and they find little or nothing amiss. Sure, they have questions about the function of a particular protein they study, or the conductivity characteristics of some new material they created. Questions, yes. But screaming? Why on Earth would they want to scream? Did something bad happen? Did someone get hurt?

Perhaps this is all for the best, in a way. Few good insights have ever come out of a truly agitated, unruly, or impatient mindset, as far as I am aware. Those who feel that they must have their answers right-now-today are often forced to settle for the very first piece of detritus that drifts by. Impatient people are left embracing Towers of Babel, Alien Invasions, and various other lightweight and ridiculous explanations of why things are the way they are. Clearly, more insightful accounts come out of greater deliberation and perseverance, but even they only provide a peek at how things might be. Whatever small insights eventually come to us usually are the result of the most deliberate and patient investigations. Scratching and clawing.

Still, there is an aspect in which this is deeply unfortunate, because it requires that human beings make careers of scientific investigation, with all the afflictions that this situation can be expected to bring. The cutting urgency to uncover the circumstances of our existence is lobotomized to the dull necessity of publishing five journal papers a year and teaching basic principles to 800 disinterested undergraduates. The impassioned crusade for Truth metamorphoses into the Post Office. The mentality becomes one of individual career advancement, of "getting by" in the institution from day to day and year to year. Perhaps somewhere in a dark recess of the researcher's mind remains a dim recollection that they thought they had something to do, but what was it?

It is possible that there is another reason for the apparent absence of panic and urgency one sees among scientists. It is possible that many scientists believe that the circumstances of our existence have been adequately explained and accounted for with the discovery of Evolution. Thus, I suppose they would say, with the Theory of Evolution in hand we need no longer feel the pressing panic and confusion of the Prisoner, because we pretty much know, at least in broad terms, how we came to be here, why the world appears the way it does, and whether there is some ultimate purpose to any of this. (Apparently not.)

But frankly, any sense of tranquility derived from the Theory of Evolution is truly undeserved. The Theory of Evolution is the very last place that we should look for comfort about our situation. The Theory tells us that the particulars of our existence and many particulars of the world around us all owe to a long-term process of environmental adaptation. But the Theory also tells us that our mind — the "citadel itself," our entire mechanism of apprehension and cognition, of knowing about the world — also owes to the very same process of environmental adaptation.

But then arises the doubt, can the mind of man, which has, as I fully believe, been developed from a mind as low as that possessed by the lowest animals, be trusted when it draws such grand conclusions? (Darwin)

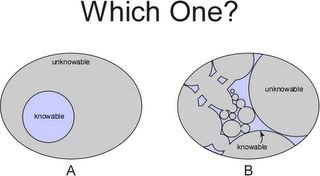

In my opinion, the evolutionary origins of the human mind throws us into an even greater state of perplexity about the circumstances of our existence. What guarantee do we have that a brain which evolved millions of years ago for tasks of hunting and mating would ever be adequate to the task of comprehending the true nature of the cosmos and our place in it? Not only can I not imagine any such guarantee, but the very notion that such a brain might possess such capacities seems ludicrous. So while the Theory of Evolution is clearly a huge advance in every regard, it gives us yet another level of perplexity: What are the constraints and biases of minds such as ours, and how can we ever characterize these constraints and biases without knowing a great many things a priori about the nature of the world that we are attempting to discover through the use of these very capacities.

What we want is to reach a position as independent as possible of who we are and where we started, but a position that can also explain how we got there. (Nagel)

It's that last part that has to give us all headaches. Who are we that our minds can discover the Truth? This is the greatest source of perplexity in the modern age. Even with all the impressive fMRI and single-cell recording studies now being done, I don't think scientists have really yet gotten a grasp of the nature of this problem. Perhaps it's best just to scream, after all.

A noiseless patient spider,

I mark'd where on a little promontory it stood isolated,

Mark'd how to explore the vacant vast surrounding,

It launch'd forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself,

Ever unreeling them, ever tirelessly speeding them.

And you O my soul where you stand,

Surrounded, detached, in measureless oceans of space,

Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing, seeking the spheres to connect them,

Till the bridge you will need be form'd, till the ductile anchor hold,

Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere, O my soul.

(Whitman, "A Noiseless Patient Spider")